TOUR 7

TOUR 7

ROUTE MAP

VIEW

TOUR 7

TOUR 7

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

TOUR 7

TOUR 7

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

TOUR 7

TOUR 7

PUBLISHED ARTICLE

VIEW

|

|

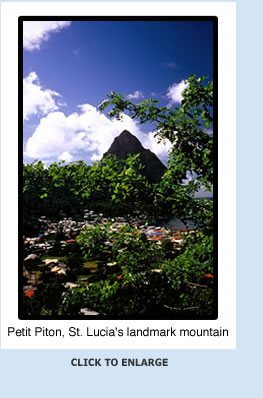

The

26-mile St. Vincent channel, between the Windward Caribbean islands of St. Lucia

and St. Vincent, is not the widest channel in the Caribbean, but it may be the

meanest. I describe it separately because in every way—in extremes of beauty, danger and challenge—this

channel stands alone. The

26-mile St. Vincent channel, between the Windward Caribbean islands of St. Lucia

and St. Vincent, is not the widest channel in the Caribbean, but it may be the

meanest. I describe it separately because in every way—in extremes of beauty, danger and challenge—this

channel stands alone.

The St. Vincent channel has a mystique, a charisma that draws sailors

and adventurers in the way that Everest attracts climbers, the north

shore of Hawaii entices surfers, and the English Channel rivets swimmers.

Challengers of the St. Vincent channel want to say, yes, they crossed

it.

Yearly, the St. Vincent channel claims lives:

weekend sailors, daredevils and drunks in small craft and sleek-muscled

windsurfers—along

with hard-bitten sailors with thousands of sea miles to their credit.

The St. Vincent channel seems to concentrate and personalize ocean

savagery and fickleness in the same way as a hurricane. It is a force

that can be measured in wave height, wind speed, and tidal surge,

but not in increments of awe and fear. Yearly, the St. Vincent channel claims lives:

weekend sailors, daredevils and drunks in small craft and sleek-muscled

windsurfers—along

with hard-bitten sailors with thousands of sea miles to their credit.

The St. Vincent channel seems to concentrate and personalize ocean

savagery and fickleness in the same way as a hurricane. It is a force

that can be measured in wave height, wind speed, and tidal surge,

but not in increments of awe and fear.

The waves in the St. Vincent channel are

always bigger than waves in neighboring channels; the wind has

a way of becoming the opposite of what is forecast. The current

can flow at up to three knots. When I told athlete/adventurer friends,

many of whom had crossed the channel on large sturdy boats, that

I planned to paddleboard across the St. Vincent channel, they said,” Don’t.”

Ship your board to either St. Lucia or St. Vincent. Follow my shipping

instructions in trips 2 and 6. If it may influence your decision

about whether to start paddling from St. Lucia or St. Vincent, let

me say that St. Vincent is extremely primitive, and it may be hard

to organize a chase boat from there.

In the spring and summer, the wind blows predominantly east/southeast and, in winter, east/northeast. In the spring (April and May) and

in the autumn (September through October) you can have flat calm

days. The biggest adverse influence that you must factor in when

you decide whether to start crossing the channel from the south end

of St. Lucia or from the north end of St Vincent, is the current.

There are tidal and equatorial currents. Tidal currents flow either

east or west depending on whether the tide is entering or leaving

the Caribbean Sea. The equatorial current is continuous and flows

west/northwest. Both currents are subject to lunar influence and

can hustle along at up to three knots, especially when the moon is

full! It is wise, before you set a paddling date to observe lunar

cycles. Island fishermen are accomplished meteorologists and can

give you good advice. Seek them out! In the spring and summer, the wind blows predominantly east/southeast and, in winter, east/northeast. In the spring (April and May) and

in the autumn (September through October) you can have flat calm

days. The biggest adverse influence that you must factor in when

you decide whether to start crossing the channel from the south end

of St. Lucia or from the north end of St Vincent, is the current.

There are tidal and equatorial currents. Tidal currents flow either

east or west depending on whether the tide is entering or leaving

the Caribbean Sea. The equatorial current is continuous and flows

west/northwest. Both currents are subject to lunar influence and

can hustle along at up to three knots, especially when the moon is

full! It is wise, before you set a paddling date to observe lunar

cycles. Island fishermen are accomplished meteorologists and can

give you good advice. Seek them out!

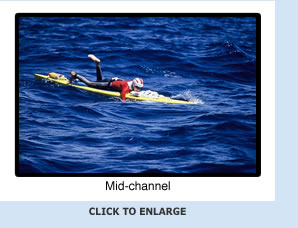

However you cross the St. Vincent channel

(unless in a mega-yacht) you will be challenged as a physical being

and wowed by the beauty and horror of it all. At mid-channel you

sit in the cobalt-and-cream ocean gripped in the scenic and climatic

crucibles of St. Vincent’s

tall, powder-blue volcano and the emerald mist that is St. Lucia--both

fifteen miles away—and maybe the fear of noting how small you

feel in the face of increasing wind, current and waves. However you cross the St. Vincent channel

(unless in a mega-yacht) you will be challenged as a physical being

and wowed by the beauty and horror of it all. At mid-channel you

sit in the cobalt-and-cream ocean gripped in the scenic and climatic

crucibles of St. Vincent’s

tall, powder-blue volcano and the emerald mist that is St. Lucia--both

fifteen miles away—and maybe the fear of noting how small you

feel in the face of increasing wind, current and waves.

Your landing and take-off spots, whether

they are on St. Lucia or St. Vincent, is something to consider.

A town called Vieux Fort on the south end of St. Lucia is a logical

jumping-off spot. It has a nice beach where you can launch. Fancy,

the north most town on St. Vincent and your logical touchdown spot,

can present problems. If there is any swell running, you won’t be able to touch the

rocky shore near Fancy, You must search for a sheltered cove—difficult

if you’ve just paddled 26-plus miles!

Wherever you start from, do it early in the morning, 2:00 a.m. or

so, to give yourself daylit margin for error when you reach the other

side of the channel.

Here is an excerpt from one of my stories:

“Susan, you go backward,” says

Ulrich Meixner. He is a tall Austrian in his late forties.

He has a hatchet face and the bloodshot eyes of the chronic sailor.

Ulli captains the sturdy fifty-foot sailing catamaran named Daedalus

that follows me in the St. Vincent channel. I had heard that this

channel is the most dangerous in the Caribbean, so I opted for

an escort boat. Ulrich’s yacht management company, DSL Yachting

on St. Lucia (along with six of his friends) eagerly supported

my adventure. They sailed me twenty miles down from Gros Ilet on

the north end of St. Lucia to where I would start paddling.

Scott Stripling, a meteorologist friend based in Puerto Rico, had

predicted light northeast winds: perfect for me to paddle south from

St. Lucia to St. Vincent. But, as I entered the St. Vincent channel

on my paddleboard from a beach at the south end of St. Lucia at 3:30

a.m., in a circle of light from my chemical light sticks (green to

the bow, red to the stern), I felt nervous. It was as if something

powerful was there in the dark water beside me. I felt that this

force would test me: If I passed the test I could cross the channel.

If I flunked? A fish jumped out of the sea and collided with my jaw

to show me that the ocean was boss. Scott Stripling, a meteorologist friend based in Puerto Rico, had

predicted light northeast winds: perfect for me to paddle south from

St. Lucia to St. Vincent. But, as I entered the St. Vincent channel

on my paddleboard from a beach at the south end of St. Lucia at 3:30

a.m., in a circle of light from my chemical light sticks (green to

the bow, red to the stern), I felt nervous. It was as if something

powerful was there in the dark water beside me. I felt that this

force would test me: If I passed the test I could cross the channel.

If I flunked? A fish jumped out of the sea and collided with my jaw

to show me that the ocean was boss.

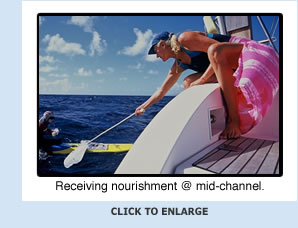

At mid-channel, I refueled with water and a sports bar brought to

me in a dinghy launched from my support boat and handed to me by

Agnes, a tall, blond, Belgian former competitive swimmer and one

of my support crew, on the end of a boat hook. I felt my night-born

superstitions vanish under the hot tropical sun. I paddled again

toward St. Vincent confident that I would soon conquer this mightiest

of channels. Suddenly, the wind switched southeast and strengthened

to fifteen knots. The ocean buckled into heavy chop and steep waves.

When took my bearings on Soufriere Hills, St. Vincent’s tall,

dormant volcano—gray and huge as a giant sleeping elephant

in the distance—and saw it move to my left, I knew that I was

being swept westward by current into the Caribbean Sea. At mid-channel, I refueled with water and a sports bar brought to

me in a dinghy launched from my support boat and handed to me by

Agnes, a tall, blond, Belgian former competitive swimmer and one

of my support crew, on the end of a boat hook. I felt my night-born

superstitions vanish under the hot tropical sun. I paddled again

toward St. Vincent confident that I would soon conquer this mightiest

of channels. Suddenly, the wind switched southeast and strengthened

to fifteen knots. The ocean buckled into heavy chop and steep waves.

When took my bearings on Soufriere Hills, St. Vincent’s tall,

dormant volcano—gray and huge as a giant sleeping elephant

in the distance—and saw it move to my left, I knew that I was

being swept westward by current into the Caribbean Sea.

Ulrich buzzed over in the dinghy and shouted that I am caught in

a three knot current and I drift backward toward St. Lucia. No way,

he insists, can reach St. Vincent. He throws me a towrope. I like

to imagine that he pulls the rope back just before I touch it. He

knows as I do that if I accept help I forfeit a “legal” channel

crossing. He goes back in mock defeat to the mother ship and I keep

paddling. Later he visits me to say that I move forward at a mile

an hour—with eleven more miles to go. “Can you paddle

for eleven more hours?” I despair, realizing that a baby can

crawl at a mile an hour. I resolve to paddle until I can paddle no

more. I concentrate on taking the next stroke. Minutes and hours

slip by as I exist in a fog of pain and determination. Time seems

both short and endless, yet the looming bulk of St. Vincent looks

increasingly defined. I can see the dark threatening shapes of rocks

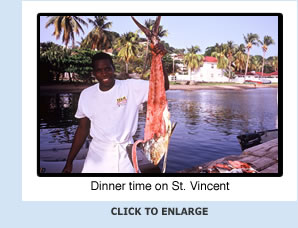

along the shore. The haze from local cooking fires winds into the

air like escaping ghosts s. I smell the rich pungent odors of roasting

meat and hear the swish and roar of breaking waves.

Ulrich buzzed over in the dinghy and shouted that I am caught in

a three knot current and I drift backward toward St. Lucia. No way,

he insists, can reach St. Vincent. He throws me a towrope. I like

to imagine that he pulls the rope back just before I touch it. He

knows as I do that if I accept help I forfeit a “legal” channel

crossing. He goes back in mock defeat to the mother ship and I keep

paddling. Later he visits me to say that I move forward at a mile

an hour—with eleven more miles to go. “Can you paddle

for eleven more hours?” I despair, realizing that a baby can

crawl at a mile an hour. I resolve to paddle until I can paddle no

more. I concentrate on taking the next stroke. Minutes and hours

slip by as I exist in a fog of pain and determination. Time seems

both short and endless, yet the looming bulk of St. Vincent looks

increasingly defined. I can see the dark threatening shapes of rocks

along the shore. The haze from local cooking fires winds into the

air like escaping ghosts s. I smell the rich pungent odors of roasting

meat and hear the swish and roar of breaking waves.

It grows dark but the lights of houses and cars on St. Vincent glimmer

ever closer. I begin to think that I can get there. The last inches

an d miles are not given to me easily. The headwind—never below

twelve miles an hour—and the racing current never let up.

I was carried twelve extra miles out into the Caribbean Sea. I often

went backward. In all, I paddled 40 nautical miles and spent 18.5

hours at sea. I started and ended my channel crossing in the pitch

dark; I witnessed the ending and beginning of two spectacularly clear

nights. I saw stars pinned to the black velvet sky like diamonds

on display. I had felt myself both bloom and wither under the sleepless

eye of the full moon. I was carried twelve extra miles out into the Caribbean Sea. I often

went backward. In all, I paddled 40 nautical miles and spent 18.5

hours at sea. I started and ended my channel crossing in the pitch

dark; I witnessed the ending and beginning of two spectacularly clear

nights. I saw stars pinned to the black velvet sky like diamonds

on display. I had felt myself both bloom and wither under the sleepless

eye of the full moon.

|

|