TOUR 8

TOUR 8

ROUTE MAPS

VIEW

TOUR 8

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

TOUR 8

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

TOUR 8

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

TOUR 8

NEWS ARTICLE

VIEW

VIEW

VIEW

|

|

Puerto

Rico is sixty miles west of Tortola, BVI. The wind in the Virgin

Islands blows predominantly, and heavily, east. Paddleboarders on

their way from Tortola to Puerto Rico will probably have the best

downwind romp of their lives. Hardcore souls may opt to paddle the

full sixty miles without stopping, but you will miss the unique people

and scenery of the Virgin Islands. A paddling tour from Tortola to

Puerto Rico visits three cultures: the British Virgin Islands, the

US Virgin islands, and—though the they belong to the USVI—the

Spanish Virgins that include Puerto Rico.

You can ship your board with Tropical Shipping

from Miami to the BVI. Tropical Shipping has an outpost in Los

Angeles that can truck your board to Miami. Mapcargo, a company

that operates out of Redondo Beach, CA, ships from both coasts

by land, air and sea to the Caribbean. If you fly your board make

sure it will fit on the plane! I learned the hard way that paddleboards

won’t fit on some aircraft.

Though fun and scenic, paddling from Tortola to Puerto Rico is

no gimme. You will paddle in crowded waters, strong currents and

wind. You will cross two over twenty-mile channels: the 25-mile

Virgin Passage between St. Thomas and Culebra and the 26 miles

of open ocean that parallel the Cordillera, a necklace of islands

strung between Culebra (part of Puerto Rico) and “mainland” Puerto

Rico.

I suggest a chase boat in the Virgin Passage

and for Culebra to Puerto Rico. Possible chase boats for the Virgin

Passage can be found in boat-for-hire sections of St. Thomas tourist

publications. Local fishermen on St. Thomas could perhaps provide

a boat. For Culebra to PR, contact boat owners and marine businesses

in Fajardo, PR, or the anchorage in Culebra. If you solo, bring

plenty of water, food, waterproof charts, compass, GPS—and

your passport. A bike flag attached to the rear of your board will

make you visible to boat traffic.

Customs and Immigration will see you as a

captain, and your board as a “ship underway”. Clear out and in with Customs and

Immigration EACH time you enter or leave a Caribbean country. On

Tortola, clear out at the ferry dock on West End. On St. John, clear

in at Cruz Bay; on St. Thomas, the ferry dock at Charlotte Amalie.

Customs and Immigration (See my story “Desiree”) can

end your trip by refusing to allow you to continue on. Customs and Immigration will see you as a

captain, and your board as a “ship underway”. Clear out and in with Customs and

Immigration EACH time you enter or leave a Caribbean country. On

Tortola, clear out at the ferry dock on West End. On St. John, clear

in at Cruz Bay; on St. Thomas, the ferry dock at Charlotte Amalie.

Customs and Immigration (See my story “Desiree”) can

end your trip by refusing to allow you to continue on.

Here is my account of crossing from Tortola to Puerto Rico:

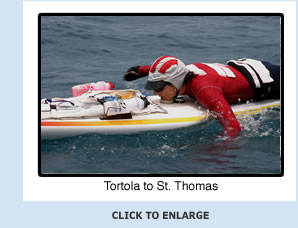

In mid-May, threatened by a thunderstorm and strong wind, I crouched,

swathed in sun-protective Lycra clothing, dark goggles and Lawrence

of Arabia headgear on the sand blasted beach at Little Apple Bay,

Tortola. I loaded my dry bags with gear and stored them in a zippered

mesh carryall bolted to the deck of my board. I poked my red bicycle

flag onto the rear of my board. Shouting over the snapping of my

little safety flag, the rumble of thunder and the frenzied rustle

in palm trees of a twenty-two knot east wind (perfect for paddling

west to Puerto Rico), I counseled my son and sister-in-law on my

paddling route. My family had come to Tortola to support me. They

hoped to follow me in ferries and whatever boat they could find to

Puerto Rico

The wind pushed big dark clouds like heavy

furniture along the flat gray floor of the sky. Big raindrops exploded

against my face and the white fiberglass deck of my board. Eli,

a dark-haired strapping 36-year old, helped me carry my laden board

into the sea. My sister-in-law, Holly, a slim toned woman in her

late sixties (She had recently overcome a leg-shattering car crash

to again win big on the senior tennis circuit.) grinned at us from

the beach. Nervous but determined to succeed, I saluted my family

and my vertiginous desert island home, Tortola, and paddled west

toward Puerto Rico. The wind hustled me past Smuggler’s Cove,

a, pearl-sanded haven on Tortola for snorkelers. I felt apprehensive

and joyful about the weather, the dangers of my trip and the possible

glory of being first to paddleboard from Tortola to Puerto Rico.

Whenever I paddle in the Caribbean, I try

to hang out in the beauty and grandeur of it all. I look up at

the stately palaces in the clouds. I ogle aquamarine water beneath

me—so luminous it must hold

the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. I imagine myself reclining

on every dark shadow under the palm trees. I hope never to provoke

Caribbean ire: the violence of tropical storms, the avarice of drug

runners, the desperation of refugees from Cuba and Haiti, the mindless

power of speedboats, known as cigarette boats, captained by minds

set to appreciate only velocity over water and the possibility of

instant wealth. Some of these desperate critters hang out in the

VI’s most spectacular coves and beaches. I make it a point

to never approach strange boats anchored in idyllic spots with the

idea of discussing the weather or making friends. Whenever I paddle in the Caribbean, I try

to hang out in the beauty and grandeur of it all. I look up at

the stately palaces in the clouds. I ogle aquamarine water beneath

me—so luminous it must hold

the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. I imagine myself reclining

on every dark shadow under the palm trees. I hope never to provoke

Caribbean ire: the violence of tropical storms, the avarice of drug

runners, the desperation of refugees from Cuba and Haiti, the mindless

power of speedboats, known as cigarette boats, captained by minds

set to appreciate only velocity over water and the possibility of

instant wealth. Some of these desperate critters hang out in the

VI’s most spectacular coves and beaches. I make it a point

to never approach strange boats anchored in idyllic spots with the

idea of discussing the weather or making friends.

I keep my eye also on the inter island ferries

whose captains want to get where they’re going quickly and are not known for their

compassion: A group of snorkelers capsized their dinghy off Big Thatch,

a small island west of Tortola. The swimmers waved desperately at

a passing ferry in the hope of rescue. The ferry captain tooted his

horn in salute and the passengers waved in greeting—as the

ferry swept past on its way to St. Thomas. Maybe, I tell myself,

the people on the ferry thought that the drowning snorkelers were

having fun. But, after fifteen years in the Caribbean, I am aware

of its dark side. Fortunately, the snorkelers were rescued by a fishing

boat.

Crossing the turbid two-hundred-yard-wide

channel (where the snorkelers almost drowned) between Tortola and

Big Thatch, I fell off my board in steep standing waves and strong

current caused by the meeting of wind and wave from the Drake Channel

and the Atlantic Ocean. Swimming, before I could re-mount my board,

I was overwhelmed by the wake of the “When” boat. This little ferry ambles several times

a day from Tortola to the neighbor isle Jost Van Dyke. It is named “When” because

it leaves Tortola “When” it wants to. The When boat exemplifies

Caribbean philosophy.

The remains of an ancient volcano, the steep

island of Big Thatch is as covered with prickles as a porcupine:

all kinds of cactus and thorn bush thrive there. The island is

home to feral cattle, sharp-horned ferocious creatures that can

challenge intruders. Along with the island’s craggy steepness and opportunistic plants that leave

you with their clingy seeds, the fierce cattle say that Big Thatch

is theirs. Sharks love Big Thatch’s west end that rises Titanic-like

in a tall black final statement of the island’s end point of

land. As I ate and drank astride my board off Big Thatch’s

west end, I saw a medium-sized shark (species unknown) well up through

the dark water beneath me. The animal passed several time under my

board like a rodeo bull, then undulated off back to deeper water. The remains of an ancient volcano, the steep

island of Big Thatch is as covered with prickles as a porcupine:

all kinds of cactus and thorn bush thrive there. The island is

home to feral cattle, sharp-horned ferocious creatures that can

challenge intruders. Along with the island’s craggy steepness and opportunistic plants that leave

you with their clingy seeds, the fierce cattle say that Big Thatch

is theirs. Sharks love Big Thatch’s west end that rises Titanic-like

in a tall black final statement of the island’s end point of

land. As I ate and drank astride my board off Big Thatch’s

west end, I saw a medium-sized shark (species unknown) well up through

the dark water beneath me. The animal passed several time under my

board like a rodeo bull, then undulated off back to deeper water.

My next challenge was the Narrows, an eighth-of-a-mile-wide

channel between Tortola and St. John, USVI. The Narrows are part

of the Drake channel that parallels Tortola and a string of neighbor

islands to the north. The Narrows dangerously concentrates diverse

boat traffic—cargo

vessels, container ships, sailboats, cigarette boats and ferries—that

makes its way between the BVI and the USVI. Amazingly, the ferry

that was bringing Eli and Holly to meet me on St. John passed me

just as, panting and adrenalized, I reached the north coast of St.

John on my paddleboard. Eli later told me that he had cautioned the

ferry captain, “There she is! Don’t hit my mom.”

Relieved to escape the Narrows, I paddled

in to a spacious bay on St. John’s north coast. I appreciated the island’s beauty.

Mostly a national park, St. John—though generously discovered

by the cruise ship set and hippie types, who (I love them for this!)

think that the sixties must be preserved in their long hair, beads,

and the peace sign—is a citadel of nature. Its pure beaches

and tangled jungles, still raucous with birds, are iconic to tropics

lovers. East of St. John’s bustling commercial hub, Cruz Bay,

are tranquil bays like Maho Bay and Cinnamon Bay. Both have campgrounds. Relieved to escape the Narrows, I paddled

in to a spacious bay on St. John’s north coast. I appreciated the island’s beauty.

Mostly a national park, St. John—though generously discovered

by the cruise ship set and hippie types, who (I love them for this!)

think that the sixties must be preserved in their long hair, beads,

and the peace sign—is a citadel of nature. Its pure beaches

and tangled jungles, still raucous with birds, are iconic to tropics

lovers. East of St. John’s bustling commercial hub, Cruz Bay,

are tranquil bays like Maho Bay and Cinnamon Bay. Both have campgrounds.

I spent the night with Holly and Eli in a

tent in Maho Bay. We refueled in the campground’s adequate, cat-infested restaurant and slept

like stones until morning—when we resumed our roles as athlete

and support team. I would paddle on to St. Thomas, where Bolongo

Bay, an all inclusive resort, had agreed to put me up for a pro bono

night. Eli and Holly planned to pursue me to St. Thomas in a ferry.

The wind seemed stronger. As I set out from Maho Bay, I lost myself

in the striations of the muscular sea. Purple-black with wind, the

water galloped so hard that flecks of white foam appeared on its

limbs like sweat on the flanks of a racehorse.

Passing the relatively calm entrance of Cruz

Bay, St. John, I joined a herd of elderly (my age!) kayakers out

with their guide on a tour of Cruz Bay. Soothed that I had at last

joined my species—folks

paddling around in the sea—I then set myself apart by informing

my newfound tribe that I was on my way to Puerto Rico. “Do

you know,” I asked my audience that looked aghast with open

mouths and bulging eyes to learn of my plans, “how to get through

the St. James Island cut?”

As crucibles go, I saw that the St. James

Island cut, off the west end of St. John and between St. Thomas

and a small out island named St. James, might be the worst problem

that I’d encounter enroute

to Puerto Rico. In order to reach the west coast of St. Thomas, most

boat traffic passes through the St James Island cut, a ravenous slot

filled with conflicting waves, current and confused boats. The mere

thought of threading the perilous eye of this needle on a vessel

as small as a kayak had the Cruz Bay kayakers paddling away from

me. They ignored me, as polite politically correct folks ignore a

grisly car crash.

On my own, I wondered how to proceed through

the St. James Island Cut. At the mouth of the cut I saw a large

swaying buoy. I figured that boats—I counted three ferries, a cigarette boat, a cargo

vessel laden with cars, and a small container ship—vying to

be first through the cut, would not want to hit the buoy, and thus

would avoid me. If I could hide behind the buoy, it would give me

a safe vantage point from which to plot my next move. When I saw

a window in the charging boat traffic, I closed my eyes and sprinted

toward the buoy. On my own, I wondered how to proceed through

the St. James Island Cut. At the mouth of the cut I saw a large

swaying buoy. I figured that boats—I counted three ferries, a cigarette boat, a cargo

vessel laden with cars, and a small container ship—vying to

be first through the cut, would not want to hit the buoy, and thus

would avoid me. If I could hide behind the buoy, it would give me

a safe vantage point from which to plot my next move. When I saw

a window in the charging boat traffic, I closed my eyes and sprinted

toward the buoy.

Feeling that it was log graciously offered to me to prevent my sure

drowning, I clutched at the buoy. It and me became the point of divergence

for oncoming boats. I saw that the best way to avoid the boats and

current (it reminded me of class five rapids) would be to quickly

attain, then hug the south coast of St. Thomas. I reached St. Thomas,

which is about fifteen miles from Tortola, by paddling as fast as

a speed boat and maximally risking my life. I began to poke along

the west coast, which is civilized enough to require, by placing

conspicuous red buoys, that boat traffic stay four hundred yards

offshore. Bolongo Bay was still twelve miles away.

Bolongo Bay teemed with avid vacationers.

I was buzzed by jet skis, avoided by windsurfers and sailboats,

and hailed by snorkelers. Bolongo Bay could be negatively described

as a stereotypical all-inclusive resort, but I felt warmed by the

staff’s friendly greeting

and the enthusiasm of my son and sister-in-law. After an interlude

of greasy food, air conditioning, TV, and a view of beach umbrellas

that sheltered the large abdomens of the indolent, I was ready to

tackle the Virgin Passage, then on to Culebra and Puerto Rio

I picked up my first chase boat outside Botany

Bay on the extreme west tip of St. Thomas. On an island known for

violent crime, racial tension, traffic congestion—and fondly called Little New York—Botany

Bay, with its lack of hotels and its thriving marine ecosystem, is

St. Thomas’s respite from civilization. I was lucky to get

a support boat for the Virgin Passage from a St. Thomas surf-related

business. My boat captain, a powerfully built grinning islander,

was eager to see me set off on my 25-mile traverse of the Virgin

Passage. I started out from a small beach and paddled toward the

low distant V of land that was Culebra. I picked up my first chase boat outside Botany

Bay on the extreme west tip of St. Thomas. On an island known for

violent crime, racial tension, traffic congestion—and fondly called Little New York—Botany

Bay, with its lack of hotels and its thriving marine ecosystem, is

St. Thomas’s respite from civilization. I was lucky to get

a support boat for the Virgin Passage from a St. Thomas surf-related

business. My boat captain, a powerfully built grinning islander,

was eager to see me set off on my 25-mile traverse of the Virgin

Passage. I started out from a small beach and paddled toward the

low distant V of land that was Culebra.

With the east wind and the westbound current

behind me, I moved along at a fast four knots. My family bolstered

my strength by offering me water and food in a long handled fishnet.

Icons of danger—a

cruise ship and a container vessel--loomed like icebergs on the horizon

but kept their distance. I felt safe and accomplished paddling in

to Ensenada Honda, a deep cleft in the island of Culebra. Holly,

Eli and I stayed in one of the colorful little inns that line the

shore of Ensenada Honda. Culebra is a comfy little place with none

of the hustle of its neighbor St. Thomas, or the impersonal size

of Puerto Rico.

Culebrians are proud of Dewey, their picturesque

laid-back village. They enjoy their national park that preserves

nature by encouraging volunteers to uproot non-native plants and

to fence off turtle egg-laying spots from trampling feet. Despite

their distaste for non-green visitors, Culebrians make visitors

feel like one of their own. In the evenings, a karaoke bar in Dewey

eagerly exports its fun and songs. People on boats anchored in

Ensenada Honda and Dewey’s residents sing

along with the karaoke singers from their boats and houses—until

the island is one big party singing the same song.

Paddling under the bridge that connects Ensenada

Honda and the town of Dewey to the open ocean between Culebra and

Puerto Rico, I felt sad to leave Culebra. On the ocean side of Dewey,

I met my second chase boat, a sleek sailing ketch. A gray-bearded

veteran of many ocean miles and his darkly tanned young girlfriend,

both natives of Puerto Rico, captained it. My gear was loaded the

night before, and Eli and Holly were already aboard. I had found

the boat by talking around in marinas and chandleries on Tortola.

A Tortolian business owner had friends in Puerto Rico, one of which

was eager to sail from PR, meet me in Culebra and escort me on to

Fajardo.

Culebra to PR was the most exciting part of my trip. Not

only were the views of the Cordillera, the silver-sanded, uninhabited

string of islets that link Culebra to PR, spectacular, but also the

weather challenged me. Caribbean wind almost never blows west, but

the big thunderstorms born in the vigorous thermals over the tall

mountains on PR can reverse weather pattern. The first half of my

paddle was done aided by easterly trade winds and mild seas. During

my last thirteen miles, towering clouds let down gyrating waterspouts

and hurled sharp spears of lightning. The west wind tore off the

tops of waves and flung them in my face. Seeing me fatigued and in

danger, Holly and Eli encouraged me to come aboard.

I did not want to disappoint my boat captain.

He was a hardcore mariner and a fiercely competitive racing sailor.

Under his exacting gaze, I soldiered on in worsening weather toward,

the dark rain shrouded bulk of Puerto Rico. When I reached Isla

Palomino, a resplendent tiny island four miles east of PR and popular

with weekend boaters, I knew that I’d reach the mainland.

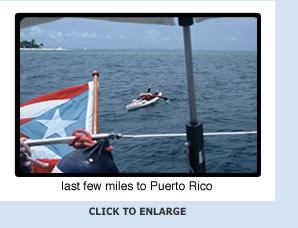

Arriving in Las Croabas, a small cove near

Fajardo, PR’s main

marina, I was met by the press from La Regata, PR’s nautical

newspaper and friends of my boat captain. Seeing grinning faces—my

captain, his pretty girlfriend and my family—above the blue

and red, single-star flag of Puerto Rico that flew from the stern

of my chase boat, I felt totally drained but proud—and already

in love with the tall, proud green island called Puerto Rico.

|

|